Artists

Hopper, Edward

“Great art is the outward expression of an inner life in the artist” - Edward Hopper

Edward Hopper, a luminary of American modern art, stands as a beacon of individuality and the power of introspection in the canon of 20th-century creativity. Hopper created his own visual language, immortalizing the silent dramas of urban life and the raw beauty of seaside houses and landscapes. Hopper’s canvases act as a window into the human condition, where light and shadow meet to reveal the profound depths of solitude and longing. His ability to distill the unique American landscape at a moment of immense change and development, both physically and emotionally, earned him a place among the best American painters. Whether in oil or watercolor, Hopper’s works invite us to ponder and marvel at the power of a single stroke to capture the ineffable essence of existence in modern-day America.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

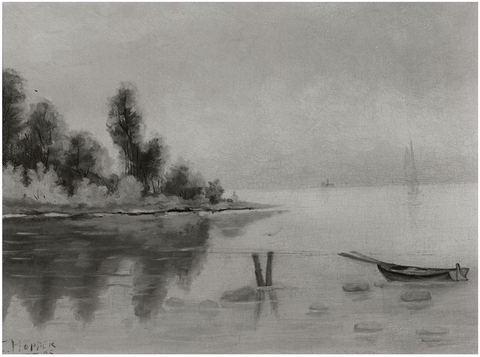

Rowboat in Rocky Cove by Hopper. 1895. Private Collection.

Edward Hopper was born in Nyack, New York on July 22, 1882. Hopper, the youngest of two children in an educated middle-class family, grew up in a supportive artistic environment that encouraged his early fascination with art. At age 10, Hopper began signing and dating his drawings, a sign of the artistic powerhouse he would later become. In 1895, at the age of 13, he created his first signed oil painting which survives today, known as Rowboat in Rocky Cove. In his teens, Hopper was quiet and reserved, immersing himself in his drawings which took a humorous tone.

In 1899, Hopper graduated high school and declared his intentions of making a career out of art. Hopper’s parents, though supportive, insisted he pursue commercial illustrations to ensure a stable income. Thus, immediately after school, Hopper enrolled in the Correspondence School of Illustrating, where he spent a brief year before abandoning illustration and focusing on his love for the fine arts. Enrolling at the New York School of Art, Hopper began taking classes under the instruction of William Merritt Chase and Robert Henri, a painter who pressured students to paint the everyday conditions of the tangible world realistically. A guiding motto of Henri’s, “It isn't the subject that counts but what you feel about it,” certainly stuck with Hopper and influenced his artistic output.

Finding His Voice: Hopper’s Struggles with Success

In 1905, Hopper began working as an illustrator in New York City for an advertising agency while trying to jumpstart his fine arts career. Although Hopper never really liked illustration, success was slowgoing for Hopper and he worked for over 20 years as an illustrator before his individual artistic career took off.

Between 1906 and 1910, Hopper traveled thrice to Europe, centering his time in Paris. While other artists favored the rising popularity of fauvism or cubism, Hopper’s time in Paris was marked by his dedication to French Impressionism, especially the works of Eduard Manet and Edgar Degas whose urban landscapes he admired. Claude Monet’s use of light had a lasting impact on the artist, and he began imitating the Impressionists by painting on the streets en plein air, or “from the fact” as Hopper called it.

Sailing by Hopper. 1911. Carnegie Museum of Art.

After arriving on his last trip in 1910, Hopper finally got to exhibit his art at the Exhibition of Independent Artists in 1910. Three years later, at age 31, Hopper exhibited in the international Armory Show of 1913, where he sold a painting, Sailing (1911), for the first time ever and exhibited among the French artists he adored. That same year, with an extra $250 from his first sale under his belt, Hopper settled into 3 Washington Square North, a home and studio he would live in for the rest of his life.

New England, Jo Nivison, and Breakthrough Recognition

Road in Maine by Hopper. 1914. Whitney Museum of American Art.

Unfortunately for the burgeoning artist, Hopper did not sell another painting for 11 years after the Armory show. In those 11 years, Hopper began spending time in New England during the summer, where the picturesque landscapes and stately homes provided ample opportunity to practice his Impressionist en plein air style, such as Road in Maine (1914). In 1920, Hopper showed his first one-person exhibition, funded by the heiress Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, at the Whitney Studio Club. While nothing was sold from the exhibition, where he mainly showed works from his time in Paris, the event became a symbolic milestone in Hopper’s career that success as an artist was possible.

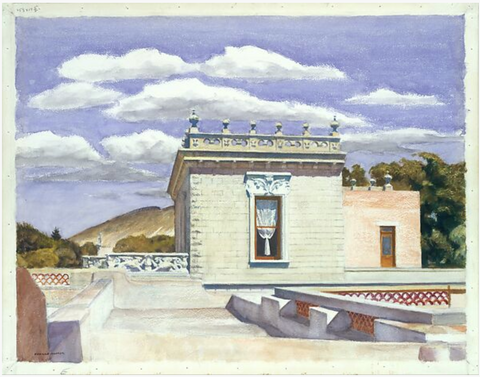

Group of Houses by Hopper. 1923-24. M.S. Rau

Then, in 1923, while living at an artist colony in Gloucester, Massachusetts, Hopper met Josephine “Jo” Nivison, a former classmate and a successful watercolorist. Hopper experimented with watercolors that summer, as seen in Group of Houses (1923/24), perhaps because of his new entanglement with Jo. That same year, when Jo was set to exhibit watercolors in the Brooklyn Museum’s International Watercolor Exhibition, Jo convinced the curators to include Hopper’s watercolors. Showing six new works, including Mansard Roof (1923), which the museum purchased, Hopper’s show was a massive success, and, finally, his career began picking up speed.

Mansard Roof by Hopper. 1923. Brooklyn Museum.

After a year-long courtship, Hopper and Nivison married on July 9, 1924, when Hopper was 41. That same year, largely due to Jo’s connections, Hopper exhibits a one-man watercolor show at the Frank K. M. Rehn Galleries in New York. The show was a massive commercial success, where Hopper sold every watercolor included. Due to the show’s success and favorable reception, Hopper finally quit his job as an illustrator and dedicated himself to art with the support of the Rehn Gallery, representing him for the rest of his life.

The Golden Years

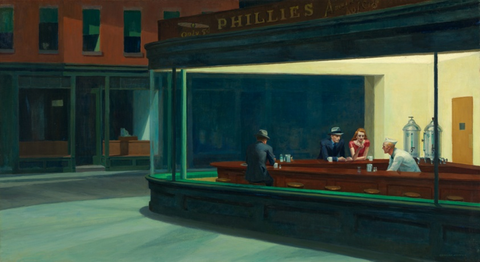

Nighthawks by Hopper. 1942. Art Institute of Chicago.

Over the next decade, Hopper dialed in his mature style, and his signature iconography emerged- from isolated figures in urban public or private interiors to sun-drenched landscapes and serene coastal lighthouses. He produced some of his most iconic works during this period, including Nighthawks (1942), a lonely scene of diners sitting in an illuminated restaurant surrounded by a desolate urban landscape. The works of this period, whose senses of silence and estrangement are rife in his darkened palette and lonely private interiors, reflect the wartime anxiety felt by Americans amidst World War II.

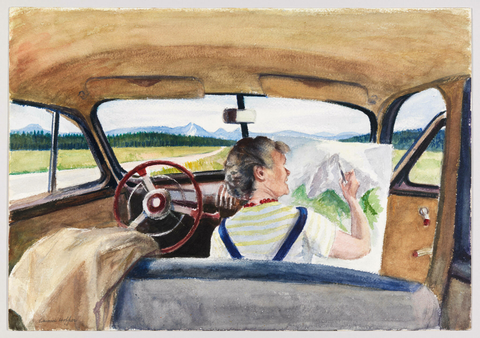

Jo in Wyoming by Hopper. 1946. Whitney Museum of American Art.

Later Life and Legacy:

Hopper continued to paint in his later years, though he found settling on a subject increasingly difficult. By the end of his life, he averaged only two oil paintings a year. In spite of this, his popularity continued despite the rise of Abstract Expressionist and Pop Art. In 1950, he was honored with a major retrospective of his work at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and in 1952, he represented the United States at the Venice Biennale International Art Exhibition. Until the end of his life, his paintings captured the overall mood of America, evoking a sense of nostalgia. When Hopper died on May 15, 1967, at the age of 84, at his Washington Square home in New York City, he was still beloved by the public and a major source of inspiration to the new generation of American realist artists. Only 10 months after his death, Jo Nivison Hopper passed away and bequeathed the entirety of their joined artistic estate to the Whitney Museum of American Art. Hopper's works can be found in most major art museums, such as the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA), the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, to name a few.