French art of the 19th century underwent a transformation that was perhaps more dramatic and revolutionary than any other moment in art history. The prevailing neoclassical style of the French Académie des Beaux-Arts came head-to-head with the emerging avant-garde Impressionist movement beginning in the 1860s, and the art world was forever changed. It was not only an aesthetic transformation, but also an ideological one as subjects and perspectives became evermore modern. The prevailing artistic trope where this transformation is perhaps most easily seen is in the female nude figure. During this time period, the female body had become more accepted, leading to a surge in nude art all over the world.

Read more: A Survey of French Art, Romanticism to the Modern Age »

For centuries, artists have turned to the female body form as an inspiration for their canvases. Yet, before the modern art era, depictions of the nude female human body were almost wholly restricted to scenes from Greek mythology – it was believed that the paganism of the ancients excused their lack of modesty. This notion persisted in the French Academy of the 19th century.

Yet, with a changing urban landscape and cultural norms, the idealized nude goddess of the Academic tradition gradually came to be replaced by more modern variations of the female nude. Rather than an object of desire, female nudity became an art form for paintings. The works that follow illustrate this extraordinary transformation for nude French art.

Leda and the Swan by Jean-Léon Gérôme

One of the most significant fine art societies in France was the Royal Academy established in 1768, and the institution held tremendous sway over the artistic tastes of the period. Academic art was rooted in the European tradition and classical art of antiquity, and young artists were instructed to develop their skills by drawing nude forms from ancient sculpture. Thus, nudity rooted in classicism became the only acceptable way, in the eyes of the Royal Academy, for the nude female form to appear in art. This work is an exceptional example and depiction of an Academic artist exploring the female nude body within a mythological context.

Composed by the great French artist Jean-Léon Gérôme, the work captures the mythological beauty Leda. While her tale is one of seduction, the anecdote plays a secondary role in this composition compared to Gérôme’s exploration of the female nude. Yet, depicted within this context with its nod to classical antiquity, such a form would have been praised rather than denounced within the strictures of the Academy.

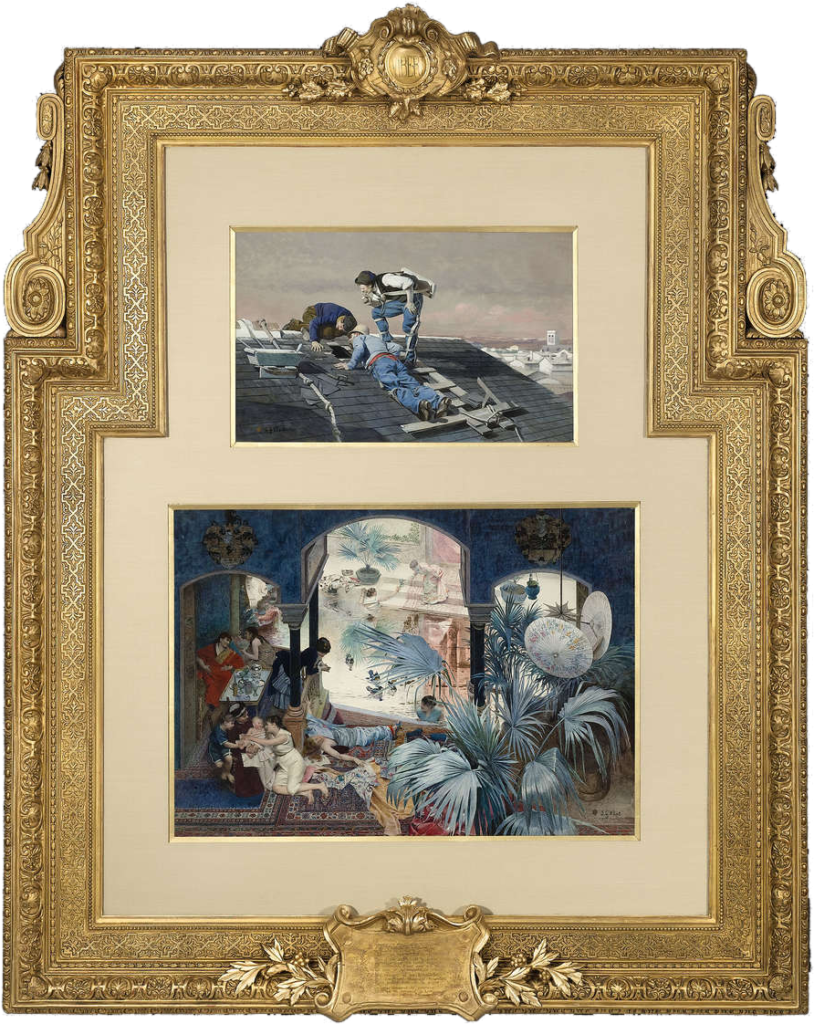

Peeping Roofers & The Woman's Bath by Jehan Georges Vibert

Peeping Roofers & The Woman’s Bath by Jehan Georges Vibert

Voyeuristic and wonderfully humorous, Academic painter Jehan Georges Vibert presents women as the object of temptation in this pair of watercolors. Lazing in an Orientalist setting that only increases their sense of exoticism, the lounging women are unaware of they are being watched from above by a group of roofers. Vibert constructs a clever commentary on the perceived dichotomy between women and men in the 19th century. Interesting, however, Vibert keeps his women fully clothed, appealing to the more traditional sensibilities of the Academy and furthering the notion of feminine innocence. While nudes in more exotic, Orientalist settings were gradually becoming acceptable in the eyes of the French public, Vibert proves himself a traditionalist in this comedic work.

Sleeping Roman Woman by Félix Auguste Clément

Femme Romaine Endormie by Félix-Auguste Clément

In the 19th century, the nude underwent its gradual evolution thanks to artists like Félix-Auguste Clément, whose Femme Romaine Endormie aspires to mythological greatness but still exudes a palpable eroticism. Clément's painting stands as an important transition point in this movement towards modernism. While she is not positioned within any specific mythological narrative, she is still surrounded by elements of antiquity – the columns behind her and rolling Italian landscape in the distance suggest a classical setting, and the style is pure Neoclassicism. Yet, her brazen nudity and evocative pose was revolutionary for its age, making this work new and groundbreaking.

Jeune Femme Nue se Coiffant by Jean-André Rixens

Composed nearly 30 years after Clément’s Femme Romaine Endormie, this extraordinary painting of a nude woman by French artist Jean-André Rixens is a testament to the dramatic transformation in French art. Both the style and subject of Rixens’ Jeune Femme Nue se Coiffant are wholly modern - the intimate scene recalls the sensuous subjects and expressive style of Rixens' contemporary, Edouard Manet. Rather than a mythological goddess from Greek mythology, the work is loosely based on Émile Zola's famed character Nana, a young red-headed courtesan first introduced in 1876. A well-known icon of French popular culture, Nana was perhaps most famously represented at her vanity by Manet in 1877, a work which now hangs in the Kunsthalle Hamburg. Deemed too lewd for public consumption, Manet's Nana was rejected by the Paris Salon of 1877, though today this painting of a naked woman is considered among his masterpieces.

Nu Allongé sur le Canapé by Henri Lebasque

Nu Allongé sur le Canapé by Henri Lebasque

Henri Lebasque’s Nu Allongé sur le Canapé embodies an entirely modern take on the female nude. The intimate scene recalls the sensuous odalisques of Lebasque's contemporary, Henri Matisse, in both its subject matter and its Fauvist palette. And, like Matisse’s nudes, the scene is entirely free from narrative. Lebasque presents a work that is not merely a portrait of a lounging nude woman, but rather an aesthetic depiction in which the figure and her surroundings are one and the same. This notion is furthered by his signature airy brushwork, which lends a dream-like softness to the voluptuous forms that fill the canvas of the nude paintings. The nude figure, as well as the sofa and the walls that surround her, are all a part of Lebasque’s artistic experimentation, and every element is equally important to make an integrated whole. With Lebasque’s nudes, the centuries-old tradition is reinvigorated, displaying a stunning color palette, flattened perspective and exclusively modern art style, making it a perfect example of nude art during this time.